Go is weird: When is a Go slice empty?

Let a be a Go slice. Under what conditions is the following

statement true: len(a) == 0?

Let a be a Go slice. Under what conditions is the following

statement true: len(a) == 0?

Here is the situation: an application maintains an in-memory cache. The cache is accessed by two threads (goroutines) concurrently. The first one constantly tries to read from the cache: very busy. The other goroutine updates the cache, relatively rarely (maybe a few times an hour). What are some synchronization/locking methods and how do they compare?

Having done extensive programming in C, I am not particularly spoiled when it comes to idiosyncrasies of a language’s “string” type. Yet, Go’s string types keeps tripping me up — why does it all still have to be that complicated?

Go request handlers typically include a “context” value as their first argument:

func handler( ctx context.Context, ... ) {

...

}

In my experience, this convention is typically fastidiously followed, but

then nothing is ever done with that ctx argument. What is it really

for? Unfortunately, the description in the official

Go package documentation

is a bit cryptic, and the type implementation itself does not reveal

anything either (the default context is just an empty struct).

Properly understood, it’s actually a really convenient idiom; however,

its value is not so much in the context package itself, but in some

idioms in the code that use the package.

Imagine a parking lot, consisting of a long, linear strip of slots. Cars enter at one end and leave by the other. Let’s also stipulate that each arriving car takes the first available slot that it encounters, that is, it will park in the first empty slot that is nearest to the parking lot entrance. Cars arrive randomly, with a given, average interarrival time $\tau_A$. Furthermore, cars occupy each slot for a random amount of time, but all with a common average dwell time $\tau_D$.

If we number the slots, starting at the entrance, we may now ask the question: what is the probability that the slot with index $n$ is occupied?

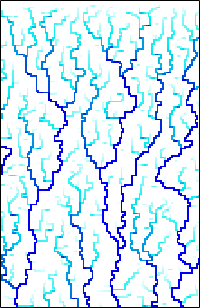

A while back, I looked at the Diamond-Square Algorithm for terrain generation. That is a purely procedural algorithm that only attempts to generate realistic looking landscapes, without trying to model any physical or geological processes. By contrast, we will now look at an algorithm to generate realistic river networks, which is based on a (simplified) model of geological erosion.

Imagine a bunch of wood chips randomly distributed on a surface. Now add an ant, randomly walking around amongst the chips. Whenever it bumps into a chip, the ant picks up the chip; if it bumps into another chip, it drops the one it is carrying and keeps walking.

How will such a system evolve over time?

A tool to display directory entries, sorted by size, together with their cumulative contribution to the total.

Go is weird. For all its intended (and frequently achieved) simplicity and straightforwardness, I keep being surprised by its rough edges and seemingly arbitrary corner cases. Here is one.

For every function, data type, or other such code artifact, there are two bits of code: the part that defines and implements it, and the one that uses it.

As I have been thinking (here and here) about the proper use and understanding of Go’s interface construct, the question came up, who is actually responsible for writing the interface: the person who defines the data type, or the person who uses it?